In the 19th century, the Mason-Dixon Line that forms the Pennsylvania-Maryland border was often seen as the invisible line between freedom and slavery. For freedom seekers like Harriet Tubman, crossing the Mason-Dixon Line into Pennsylvania represented a step into a better world.

Tubman, who was enslaved by Edward Brodess in Maryland, made a bold escape to freedom in 1849, heading north from the Eastern Shore into Delaware until she crossed into Pennsylvania, a free state. It was where she first gained her freedom, and where she first worked to support herself without paying her slaveholder for the “privilege” of doing so. She saved what she could from working as a domestic worker in Philadelphia, and crossed back over the Mason-Dixon Line on her first of at least thirteen missions to rescue family and friends and become the most famous conductor on the Underground Railroad.

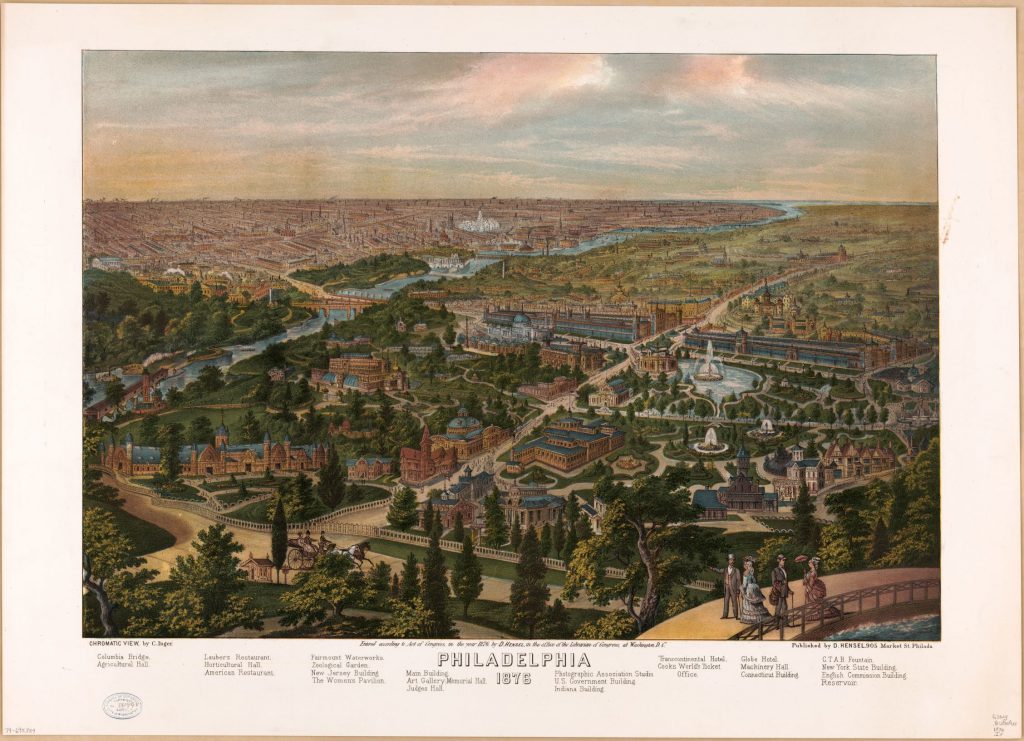

Philadelphia in 1876, courtesy of the Library of Congress

But Tubman was not able to permanently settle in Philadelphia. Soon after arriving in the city, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which made law enforcement throughout the nation cooperate with slaveholders intent on finding freedom seekers and returning them into bondage. Given its proximity to the slave states of Maryland and Delaware and the slavecatchers already active there for decades, Philadelphia was no longer the safe haven it was when she arrived. Tubman would ultimately bring most of those she rescued to Auburn, New York, or southern Ontario, Canada. Abolitionists made Auburn comparatively safe, and the Fugitive Slave Act did not apply in Canada.

There were still many in Philadelphia that opposed slavery and helped Harriet Tubman on her rescue missions. Underground Railroad conductor William Still operated a secret station for freedom seekers at 244 South 12th Street and assisted Tubman many times. Still’s station would become Tubman’s go-to stop whenever she led freedom seekers through Philadelphia. He would provide assistance to many people that Tubman brought north, including the Ennals family and Tubman’s parents. Many free Blacks like Still were conductors on the Underground Railroad, and in a few rare cases enslaved Blacks were as well.

White community members in Philadelphia, especially Quakers, also worked on the Underground Railroad and helped Tubman on her missions. Tubman’s friend Lucretia Mott was a Quaker woman who assisted Tubman throughout her life. A steamboat captain once wrote Tubman a pass stating that she was free and living in Philadelphia to allow her to travel across the Mason-Dixon Line to rescue an enslaved woman in Baltimore.

Despite being denied the right to vote, during her time in the city Tubman was politically and militarily active as well. She likely attended the National Colored Convention in Philadelphia in 1855, along with other notable figures like Frederick Douglass and William Still. Many attendees, including Tubman, also visited Underground Railroad conductor Passmore Williamson while he was imprisoned in Moyamensing Prison at the corner of 11th Street and Passyunk Avenue in Philadelphia. Until the end of her life, Tubman worked for civil rights and women’s rights, giving persuasive lectures throughout the Mid-Atlantic.

When the Civil War broke out, Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts realized that Tubman’s skill as a conductor on the Underground Railroad could be put to use for the war effort, and arranged for her to travel to South Carolina. There she worked as a spy, scout, and nurse for the U.S. Army and became the first American woman to lead an armed raid, in the process freeing over seven hundred enslaved people. Returning from leave in Auburn to visit family, in April 1865 Tubman gave an address at Camp William Penn in La Mott to the United States Colored Troops 24th Regiment about her service in the war. Coincidentally, her future husband Nelson Davis had enlisted at that same camp in 1863.

In honor of Tubman’s 200th anniversary, the City of Philadelphia recently unveiled a 9-foot sculpture called “Harriet Tubman – The Journey to Freedom.” But as we all know, Harriet Tubman’s road went far beyond the City of Brotherly Love.

Quoted by author Sarah Hopkins Bradford in 1869, Tubman said: “I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land; and my home after all, was down in Maryland; because my father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were there. But I was free, and they should be free.”

Adam Larson is a former Seasonal Park Ranger at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park in Church Creek, Maryland. An earlier version of this article originally appeared in Philadelphia Weekly in June 2021.

Article appears in Vol. 25, No. 2 of the Maryland Natural Resource magazine.

Tubman, who was enslaved by Edward Brodess in Maryland, made a bold escape to freedom in 1849, heading north from the Eastern Shore into Delaware until she crossed into Pennsylvania, a free state. It was where she first gained her freedom, and where she first worked to support herself without paying her slaveholder for the “privilege” of doing so. She saved what she could from working as a domestic worker in Philadelphia, and crossed back over the Mason-Dixon Line on her first of at least thirteen missions to rescue family and friends and become the most famous conductor on the Underground Railroad.

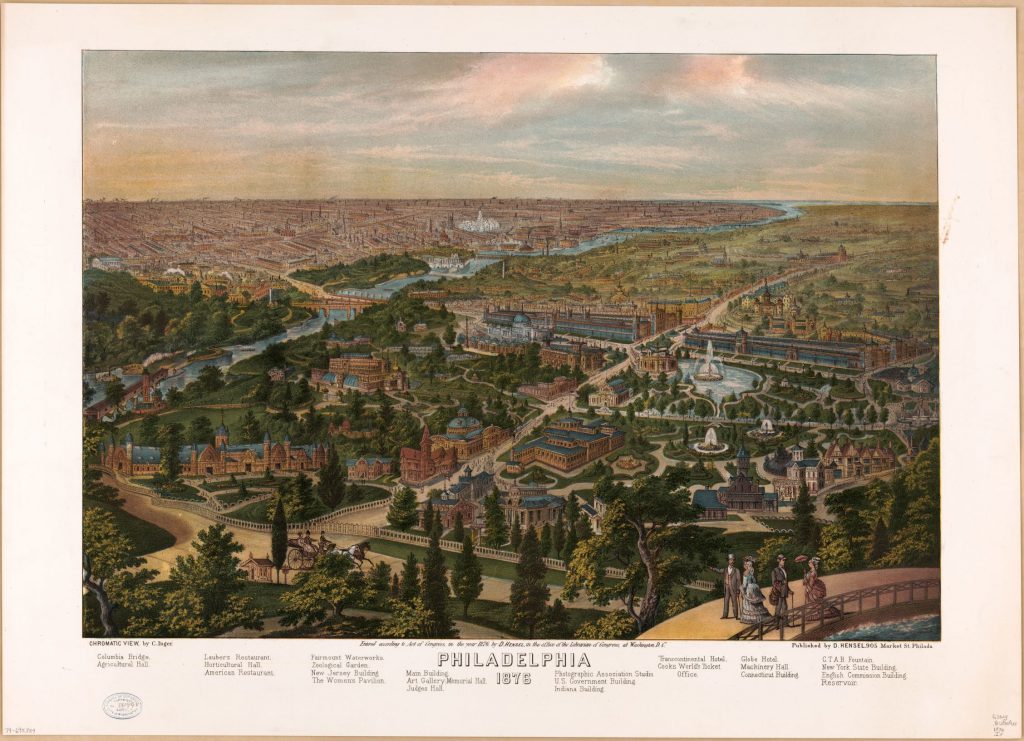

Philadelphia in 1876, courtesy of the Library of Congress

But Tubman was not able to permanently settle in Philadelphia. Soon after arriving in the city, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which made law enforcement throughout the nation cooperate with slaveholders intent on finding freedom seekers and returning them into bondage. Given its proximity to the slave states of Maryland and Delaware and the slavecatchers already active there for decades, Philadelphia was no longer the safe haven it was when she arrived. Tubman would ultimately bring most of those she rescued to Auburn, New York, or southern Ontario, Canada. Abolitionists made Auburn comparatively safe, and the Fugitive Slave Act did not apply in Canada.

There were still many in Philadelphia that opposed slavery and helped Harriet Tubman on her rescue missions. Underground Railroad conductor William Still operated a secret station for freedom seekers at 244 South 12th Street and assisted Tubman many times. Still’s station would become Tubman’s go-to stop whenever she led freedom seekers through Philadelphia. He would provide assistance to many people that Tubman brought north, including the Ennals family and Tubman’s parents. Many free Blacks like Still were conductors on the Underground Railroad, and in a few rare cases enslaved Blacks were as well.

White community members in Philadelphia, especially Quakers, also worked on the Underground Railroad and helped Tubman on her missions. Tubman’s friend Lucretia Mott was a Quaker woman who assisted Tubman throughout her life. A steamboat captain once wrote Tubman a pass stating that she was free and living in Philadelphia to allow her to travel across the Mason-Dixon Line to rescue an enslaved woman in Baltimore.

Despite being denied the right to vote, during her time in the city Tubman was politically and militarily active as well. She likely attended the National Colored Convention in Philadelphia in 1855, along with other notable figures like Frederick Douglass and William Still. Many attendees, including Tubman, also visited Underground Railroad conductor Passmore Williamson while he was imprisoned in Moyamensing Prison at the corner of 11th Street and Passyunk Avenue in Philadelphia. Until the end of her life, Tubman worked for civil rights and women’s rights, giving persuasive lectures throughout the Mid-Atlantic.

When the Civil War broke out, Governor John Andrew of Massachusetts realized that Tubman’s skill as a conductor on the Underground Railroad could be put to use for the war effort, and arranged for her to travel to South Carolina. There she worked as a spy, scout, and nurse for the U.S. Army and became the first American woman to lead an armed raid, in the process freeing over seven hundred enslaved people. Returning from leave in Auburn to visit family, in April 1865 Tubman gave an address at Camp William Penn in La Mott to the United States Colored Troops 24th Regiment about her service in the war. Coincidentally, her future husband Nelson Davis had enlisted at that same camp in 1863.

In honor of Tubman’s 200th anniversary, the City of Philadelphia recently unveiled a 9-foot sculpture called “Harriet Tubman – The Journey to Freedom.” But as we all know, Harriet Tubman’s road went far beyond the City of Brotherly Love.

Quoted by author Sarah Hopkins Bradford in 1869, Tubman said: “I had crossed the line. I was free; but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land; and my home after all, was down in Maryland; because my father, my mother, my brothers, and sisters, and friends were there. But I was free, and they should be free.”

dnr.maryland.gov/parks

Adam Larson is a former Seasonal Park Ranger at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park in Church Creek, Maryland. An earlier version of this article originally appeared in Philadelphia Weekly in June 2021.

Article appears in Vol. 25, No. 2 of the Maryland Natural Resource magazine.