Story by Laurie Pearson, Marine Corps Logistics Base Barstow

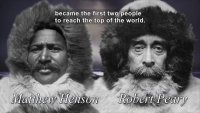

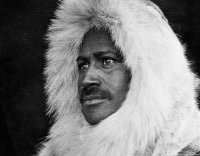

Matthew Alexander Henson, the son of two freeborn black sharecroppers in Charles County, Maryland, was one of two U.S. citizens and four Inuit assistants who became the first human beings to set foot on the North Pole on April 6, 1909.

Henson was born August 8, 1866, but lost his mother at an early age. When Henson was 4-years-old, his father moved the family to the District of Columbia, in search of better work opportunities. His father died there a few years later, leaving Henson and his siblings in the care of other family members. At the age of 11, Henson ran away from his widowed stepmother and was taken in by another woman in the area.

After working briefly in a restaurant, Henson walked to Baltimore, Maryland, where he found work as a cabin boy on the ship Katie Hines. Captain Childs, the ship’s skipper, took Henson under his wing and saw to his education, which included the finer points of seamanship. During his time aboard the ship, he saw much of the world, to include Asia, Africa and Europe.

When Childs died in 1884, Henson returned to the District of Columbia where he worked several jobs, finally as that of a clerk in a hat shop. While working in this shop, Hanson met Robert Edwin Peary, an explorer and officer in the U.S. Navy Corps of Civil Engineers, in 1887. Peary was impressed by Henson's seafaring credentials and hired him as his valet for an upcoming expedition to Nicaragua. Thus began a long working relationship that spanned half a dozen epic voyages over two decades for the team. Henson was with Peary for eight arctic expeditions over 22 years.

After returning from Nicaragua, Peary found Henson work in Philadelphia, and in April 1891 Henson married Eva Flint. But shortly thereafter, Henson joined Peary again, for an expedition to Greenland. While there, Henson embraced the local Eskimo culture, learning the language and the natives' Arctic survival skills over the course of the next year.

Their next trip to Greenland came in 1893, this time with the goal of charting the entire ice cap. The two-year journey almost ended in tragedy, with Peary's team on the brink of starvation; members of the team managed to survive by eating all but one of their sled dogs. Despite this perilous trip, the explorers returned to Greenland in 1896 and 1897, to collect three large meteorites they had found during their earlier quests, ultimately selling them to the American Museum of Natural History and using the proceeds to help fund their future expeditions. However, by 1897 Henson's frequent absences were taking their toll on his marriage, and he and Eva divorced.

Over the next several years, Peary and Henson would make multiple attempts to reach the North Pole. Their 1902 attempt proved tragic, with six Eskimo team members perishing due to a lack of food and supplies. However, they made more progress during their 1905 trip: Backed by President Theodore Roosevelt and armed with a then state-of-the-art vessel that had the ability to cut through ice, the team was able to sail within 175 miles of the North Pole. Melted ice blocking the sea path thwarted the mission’s completion, forcing them to turn back. Around this time, Henson fathered a son, Anauakaq, with an Inuit woman, but back at home in 1906 he married Lucy Ross.

The team's final attempt to reach the North Pole began in 1908. Henson proved an invaluable team member, building sledges and training others on their handling. Of Henson, expedition member Donald Macmillan once noted, "With years of experience equal to that of Peary himself, he was indispensable."

The expedition continued into the following year, and while other team members turned back, Peary and Henson trudged on.

“Henson must go all the way,” Peary said. “I can't make it there without him."

On April 6, 1909, Peary, Henson, four Eskimos and and 133 dogs) finally reached the North Pole with Henson planting the American flag. He recorded his Arctic memoirs in 1912, in the book A Negro Explorer at the North Pole.

After his exploring days Henson worked as an official in the U.S. Customs House in New York City. In 1937, a 70-year-old Henson finally received the acknowledgment he deserved: The highly regarded Explorers Club in New York accepted him as an honorary member. In 1944 he and the other members of the expedition were awarded a Congressional Medal. He worked with Bradley Robinson to write his biography, Dark Companion, which was published in 1947.

Henson died in 1955. After his death, he was buried in New York City's Woodlawn Cemetery. In 1968, the body of his wife Lucy Ross Henson was buried nearby. In 1987, at the request of Dr. S. Allen Counter of Harvard University, President Ronald Reagan granted permission for the bodies of Henson and his wife to be re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery.On April 6, 1988, the remains of Matthew Henson and his wife were transported to and re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Washington D.C., among other U.S. heroes and near the grave site of Robert Peary and his wife Josephine Deibitsch Peary. Members of Henson's family attended the ceremony along with many of the explorer's admirers from around the world. The re-interment represented the ultimate national recognition that Henson had so long deserved.

In 1996, an oceanographic survey ship was named the U.S.N.S Henson in his honor.

In 2000, Henson was posthumously awarded National Geographic’s highest honor for exploration, the Hubbard Medal.

Sources: https://www.biography.com/people/matthew-henson-9335648

news.nationalgeographic.com

news.nationalgeographic.com

Matthew Alexander Henson, the son of two freeborn black sharecroppers in Charles County, Maryland, was one of two U.S. citizens and four Inuit assistants who became the first human beings to set foot on the North Pole on April 6, 1909.

Henson was born August 8, 1866, but lost his mother at an early age. When Henson was 4-years-old, his father moved the family to the District of Columbia, in search of better work opportunities. His father died there a few years later, leaving Henson and his siblings in the care of other family members. At the age of 11, Henson ran away from his widowed stepmother and was taken in by another woman in the area.

After working briefly in a restaurant, Henson walked to Baltimore, Maryland, where he found work as a cabin boy on the ship Katie Hines. Captain Childs, the ship’s skipper, took Henson under his wing and saw to his education, which included the finer points of seamanship. During his time aboard the ship, he saw much of the world, to include Asia, Africa and Europe.

When Childs died in 1884, Henson returned to the District of Columbia where he worked several jobs, finally as that of a clerk in a hat shop. While working in this shop, Hanson met Robert Edwin Peary, an explorer and officer in the U.S. Navy Corps of Civil Engineers, in 1887. Peary was impressed by Henson's seafaring credentials and hired him as his valet for an upcoming expedition to Nicaragua. Thus began a long working relationship that spanned half a dozen epic voyages over two decades for the team. Henson was with Peary for eight arctic expeditions over 22 years.

After returning from Nicaragua, Peary found Henson work in Philadelphia, and in April 1891 Henson married Eva Flint. But shortly thereafter, Henson joined Peary again, for an expedition to Greenland. While there, Henson embraced the local Eskimo culture, learning the language and the natives' Arctic survival skills over the course of the next year.

Their next trip to Greenland came in 1893, this time with the goal of charting the entire ice cap. The two-year journey almost ended in tragedy, with Peary's team on the brink of starvation; members of the team managed to survive by eating all but one of their sled dogs. Despite this perilous trip, the explorers returned to Greenland in 1896 and 1897, to collect three large meteorites they had found during their earlier quests, ultimately selling them to the American Museum of Natural History and using the proceeds to help fund their future expeditions. However, by 1897 Henson's frequent absences were taking their toll on his marriage, and he and Eva divorced.

Over the next several years, Peary and Henson would make multiple attempts to reach the North Pole. Their 1902 attempt proved tragic, with six Eskimo team members perishing due to a lack of food and supplies. However, they made more progress during their 1905 trip: Backed by President Theodore Roosevelt and armed with a then state-of-the-art vessel that had the ability to cut through ice, the team was able to sail within 175 miles of the North Pole. Melted ice blocking the sea path thwarted the mission’s completion, forcing them to turn back. Around this time, Henson fathered a son, Anauakaq, with an Inuit woman, but back at home in 1906 he married Lucy Ross.

The team's final attempt to reach the North Pole began in 1908. Henson proved an invaluable team member, building sledges and training others on their handling. Of Henson, expedition member Donald Macmillan once noted, "With years of experience equal to that of Peary himself, he was indispensable."

The expedition continued into the following year, and while other team members turned back, Peary and Henson trudged on.

“Henson must go all the way,” Peary said. “I can't make it there without him."

On April 6, 1909, Peary, Henson, four Eskimos and and 133 dogs) finally reached the North Pole with Henson planting the American flag. He recorded his Arctic memoirs in 1912, in the book A Negro Explorer at the North Pole.

After his exploring days Henson worked as an official in the U.S. Customs House in New York City. In 1937, a 70-year-old Henson finally received the acknowledgment he deserved: The highly regarded Explorers Club in New York accepted him as an honorary member. In 1944 he and the other members of the expedition were awarded a Congressional Medal. He worked with Bradley Robinson to write his biography, Dark Companion, which was published in 1947.

Henson died in 1955. After his death, he was buried in New York City's Woodlawn Cemetery. In 1968, the body of his wife Lucy Ross Henson was buried nearby. In 1987, at the request of Dr. S. Allen Counter of Harvard University, President Ronald Reagan granted permission for the bodies of Henson and his wife to be re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery.On April 6, 1988, the remains of Matthew Henson and his wife were transported to and re-interred at Arlington National Cemetery, Washington D.C., among other U.S. heroes and near the grave site of Robert Peary and his wife Josephine Deibitsch Peary. Members of Henson's family attended the ceremony along with many of the explorer's admirers from around the world. The re-interment represented the ultimate national recognition that Henson had so long deserved.

In 1996, an oceanographic survey ship was named the U.S.N.S Henson in his honor.

In 2000, Henson was posthumously awarded National Geographic’s highest honor for exploration, the Hubbard Medal.

Sources: https://www.biography.com/people/matthew-henson-9335648

Matthew Henson, Pioneering Black Polar Explorer, in Historic Pictures

Largely ignored for nearly a century, Matthew Henson made big contributions to polar exploration.