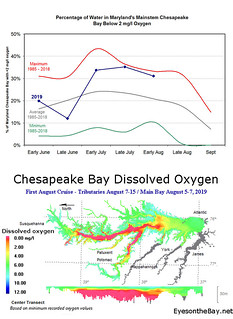

Lower dissolved oxygen throughout the Maryland portion of the bay was the result of many factors. Larger than average hypoxia was predicted for this summer in part due to high flows into the Chesapeake Bay last fall and into the spring, which delivered higher nutrient loads. Those nutrients fuel algal blooms which die and are consumed by bacteria, which then deplete oxygen in bottom waters. Surface water temperatures in the open Bay were still quite warm, about 84 degrees. Warmer waters hold less oxygen. There were no sustained wind events since the late July sampling period, which prevented oxygen from mixing into deeper waters. Finally, surface salinities are still below average for Maryland’s main bay which creates a more stratified water column, essentially acting as a cap to prevent higher oxygen surface waters from mixing with deeper, oxygen depleted waters.

Crabs, fish, oysters and other creatures in the Chesapeake Bay require oxygen to survive. Scientists and natural resource managers study the volume and duration of bay hypoxia to determine possible impacts to bay life. Each year from June to September the Maryland Department of Natural Resources computes these volumes from data collected by Maryland and Virginia monitoring teams during twice-monthly monitoring cruises. Data collection is funded by these states and the Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program. Bay hypoxia monitoring and reporting will continue through the summer.