The Maryland Department of Natural Resources Research Vessel Kehrin is used for summer hypoxia monitoring.

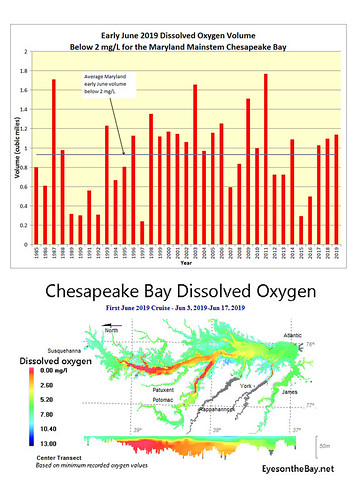

Dissolved oxygen conditions in the Maryland portion of the Chesapeake Bay mainstem were slightly above the long-term average in early June. The hypoxic water volume — areas with less than 2 mg/l oxygen — was 1.14 cubic miles, which is slightly above the early June 1985-2018 average of 0.93 cubic miles and similar to levels in 2017 and 2018.

A significant amount of hypoxia was also observed during May. Hypoxia was not observed in Virginia’s portion of the bay, and no anoxic zones — areas with less than 0.2 mg/l oxygen — were detected in the mainstem bay in either Maryland or Virginia.

The observed early June and May hypoxia conditions are likely attributable to near record high flows in 2018 that continued into the spring of 2019.

Heavy rainfall and runoff delivers more nutrients, which fuels algal blooms, and in turn consumes oxygen upon their decay. The delivery of high volumes of fresh water also acts to increase water column stratification that can inhibit atmospheric oxygen in the surface layers from mixing into deeper waters of the bay.

Crabs, fish, oysters, and other creatures in the Chesapeake Bay require oxygen to survive. Scientists and natural resource managers study the volume and duration of bay hypoxia to determine possible impacts to bay life. Each year from June through September, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources computes these volumes from data collected by Maryland and Virginia monitoring teams during twice-monthly monitoring cruises. Data collection is funded by these states and the Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program.

Bay hypoxia monitoring and reporting will continue through the summer.

[ This article originally appeared here ]