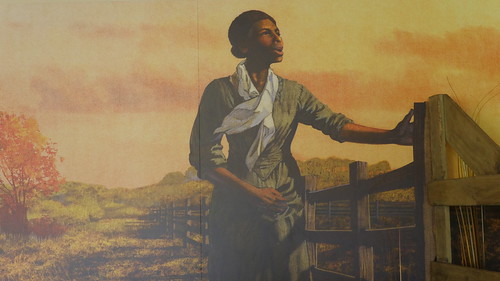

Today, Harriet Tubman is known for her heroic exploits on the Underground Railroad, where she rescued 70 people from slavery and guided them to freedom. While most of her time in Maryland was spent on the Eastern Shore, Baltimore figured centrally in several of her daring rescue missions.

Today, Harriet Tubman is known for her heroic exploits on the Underground Railroad, where she rescued 70 people from slavery and guided them to freedom. While most of her time in Maryland was spent on the Eastern Shore, Baltimore figured centrally in several of her daring rescue missions.Tubman was born enslaved in Dorchester County, and endured cruel family separations and violent abuse from slaveholders and overseers. When Tubman’s slaveholder Edward Brodess died in 1849, his widow Eliza Brodess inherited his many debts. Indebted slaveholders would often sell those they enslaved to cover what they owed, often to slave traders. Many of the enslaved were then taken hundreds of miles from their families to plantations in the Deep South. This precarious situation led Tubman to decide that she was going to leave slavery behind and gain her freedom, and later that year she fled the Eastern Shore and temporarily settled in Philadelphia.

Tubman was part of a large informal network of free and enslaved Blacks in the region that was capable of sharing information over long distances, and this network was critical to her work on the Underground Railroad. Rampant discrimination on land led many free Blacks to work in the relative freedom of the Chesapeake Bay as watermen, and their mobility on the water connected free and enslaved communities throughout the area. Through this network, in December of 1850, Tubman received word that her niece Kessiah and her two children were going to be sold. Tubman quickly traveled to Baltimore to hatch a plan to rescue her niece. Baltimore was home to a small community of African-Americans from Tubman’s native Dorchester County, including Tubman’s brother-in-law Tom. Working at the docks and on the water, the community functioned as a temporary base for Tubman as she planned the first of what would eventually total at least 13 rescue missions.

Tubman devised a plan with Kessiah’s husband, John Bowley. At the Dorchester County Courthouse on the Eastern Shore, Kessiah and her two children were sold at auction to the highest bidder. But when the auctioneer returned from dinner to complete the transaction, Kessiah, her children, and the buyer were all gone. The high bid had been placed by John Bowley, and while the auctioneer was busy eating, Bowley guided his wife and children to a nearby safehouse. They then boarded a canoe and paddled their way up the frigid Chesapeake to Baltimore, where they met up with Tubman, who guided them to Philadelphia.

The next year, Tubman returned to Baltimore and orchestrated a second mission, successfully rescuing her brother and two others from the Eastern Shore without having to leave the city. Baltimore was also the starting point for fellow abolitionist and Eastern Shore native Frederick Douglass’ flight to freedom. Later, Douglass likely provided aid to a large group of freedom seekers Tubman was guiding north in 1851. Douglass greatly admired Tubman for her intelligence and bravery noting that while he worked in the limelight, at that time her exploits were not as widely renowned.

Tubman’s final trip to Baltimore might have been her most dangerous and complicated rescue mission. Around the same time that Tubman freed herself, an enslaved man in Baltimore also fled north to avoid being sold to plantations in the Deep South, but he had to leave behind his fiancée, Tilly. In 1856, the man gave Tubman funds to rescue his fiancée and bring her to Canada. Tubman headed south to Philadelphia, where a steamboat captain gave her papers stating that she was a free resident of that city. Next, she headed to Baltimore and found Tilly, but Tubman didn’t have a similar document for her.

Instead of heading north, Tubman booked passage on a ship headed south to Seaford, Delaware. Tubman was able to convince the captain of this ship to write papers for Tilly, possibly because a pair of Black women headed south seemed unlikely to be engaged in an escape attempt. In Seaford, they were accosted by a slave trader, but upon showing their papers they were allowed to pass, and took a train and carriages driven by Underground Railroad agents to fellow agent Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware. 162 years later, Harriet Tubman Grove was dedicated in Baltimore, honoring her for her rescue missions, activism, and military service.

dnr.maryland.gov/publiclands

Adam Larson served as a 2021 seasonal ranger at Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park. Article appears in Vol. 25, No. 1 of the Maryland Natural Resource magazine.