An iconic fish begins its life cycle

Maryland Department of Natural Resources biologists Marisa Ponte, Jim Uphoff, and Shannon Moorhead traverse the quiet Choptank River, casting out a net to collect samples of striped bass eggs and larvae. Photo by Joe Zimmermann, Maryland DNR.

Laughing gulls circled and cawed in anticipation. An osprey hauled an improbably large branch through bright green treetops. It was Earth Day, April 22, and the living things on the Choptank River that bisects Maryland’s Eastern Shore marked the event by going on as usual.

But below the water’s surface, a process was underway that repeats every year in the rivers of the Chesapeake Bay, a modest beginning to a mythic Mid-Atlantic cycle, one that powers fisheries and attracts recreational anglers up and down the coast. Another generation of striped bass had come into the world.

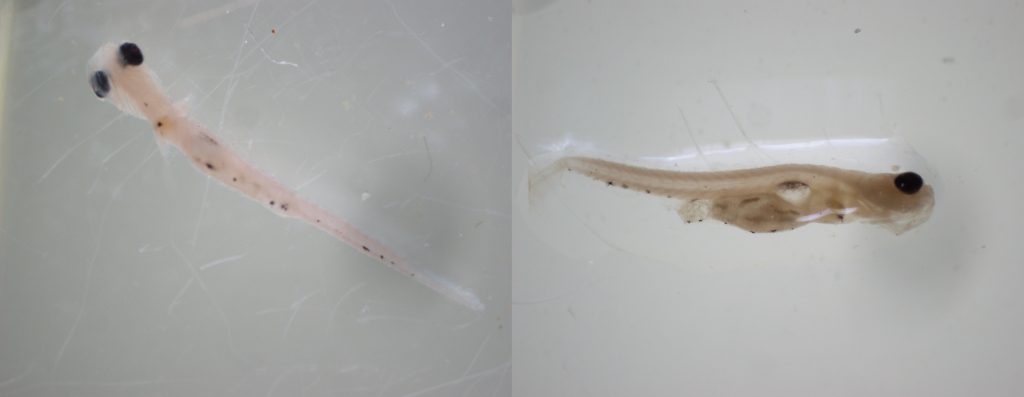

At this stage, the striped bass are miniscule, measured in the millimeters. Only days old, they look like living eyelashes wiggling in the water, tiny lines topped with two dots of eyeballs. Without a microscope, it’s difficult to tell them apart from white perch, which float alongside them and predate their entry into the world by a week or two. Striped bass eggs are little gelatinous globes, smaller than the head of a pencil eraser.

Usually mingled with the rest of the river’s murk, these larvae and eggs were brought into full sunlit view in the jars and trays of Maryland Department of Natural Resources biologists. The group was conducting a survey of the earliest life stages of striped bass, also known as rockfish in Maryland.

“The first three weeks of life are when the big things happen,” said Jim Uphoff, a DNR natural resources biologist, who leads the survey. “It can be very informative.”

This is when fish eat their first meals and are especially sensitive to pollution. Uphoff said that this stage is so critical that after three weeks, when striped bass are only 10 millimeters long, their abundance lines up with later estimates of the size of the year-class. These three weeks “determine year-class success,” he said.

And that success has commanded a lot of attention. DNR’s annual juvenile striped bass survey, a separate survey conducted in the summer when the young are larger fingerlings, has found five consecutive years of low spawning success for the species in the Chesapeake, resulting in management action to protect the adult spawning stock.

Maryland’s state fish, striped bass are the state’s most economically important finfish and hold cultural significance as a beloved catch for the recreational fishing community. They’re a sport and commercial fish up and down the East Coast, but between 70% and 90% of the Atlantic population of the species spawns in the tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay.

Striped bass larvae viewed under a microscope. In the right, a gut full of food is visible. Photos by Shannon Moorhead/DNR

Uphoff’s team uses the Choptank as a reference system because of the rich historical data available from that river, which is also part of the juvenile striped bass index. The department and other research institutions have collected data there over different surveys since 1955 on variables including water quality, egg and larval catch, and larval feeding. In 1994, the department launched an egg presence-absence survey.

In 2023, they added larval striped bass to the survey to examine how well they feed. This data gives biologists a snapshot of egg and larval success over time, as well as comparing that to factors like water temperature and food availability.

“That gives us a lot of data to compare to,” Uphoff said. “We adapted our egg and water quality survey into a way to test some of the egg- and larval habitat-related hypotheses for five years of poor spawning success.”

Setting out in a 21-foot boat, the team zipped up and down the river and the Tuckahoe Creek to predetermined sites that they check through the spring. Once they arrived at the coordinates, biologists Shannon Moorhead and Marisa Ponte prepared their equipment.

They dropped a multimeter into the water to get readings for temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and pH. Then they released a cone-shaped plankton net behind the boat as Uphoff put the boat in gear, slowly dragging the net, which has mesh so fine that even microscopic organisms can’t pass through.

After two minutes, they pulled the line back in, lifted the net up, and splashed it with water to push all the material inside into a container screwed into an adaptor at its tip: a standard mason jar.

The biologists poured the contents of the jar into a tray, where they could sift through the tiny green flecks of marsh vegetation in search of eggs. Many eggs at this point had a deflated look—most of the spawning in this area was over and eggs had already hatched into yolk-sac larvae, while the eggs that remained were largely nonviable.

Having examined the draw carefully, they dumped the tray back in the water. On a chart, Ponte and Moorhead recorded the readings from the multimeter and noted simply the presence or absence of striped bass eggs and larvae. That makes it easy to compare across sites over time, but they also separately track intensity to differentiate major from minor spawning peaks.

A jar full of vegetation that the team will sift through for signs of the striped bass spawn. Photo by Joe Zimmermann

Then it’s off to the next site. Part of the success of the survey is how it only takes a small crew, working a small boat with minimal gear. “You don’t need a whole lot of fancy equipment,” Ponte said.

They repeated the process at 10 sites, then used a longer net at a higher speed at three more sites. These pulls brought in larger larvae that the cone-shaped nets do not catch well, and they preserved these samples with formaldehyde to bring back to the lab for analysis. These removals give their research an adequate sample size, but amount to a fraction of a fraction of the overall spawn. The team has a few more days of data collection for this year, then they’ll work on analyzing what they’ve found.

In the lab, they count the scaled-down stripers, differentiate them from white perch—and also look at their stomach contents. Under a microscope, the biologists tease the guts apart so they can see what food is present, mainly cladocerans and copepods, freshwater planktonic crustaceans.

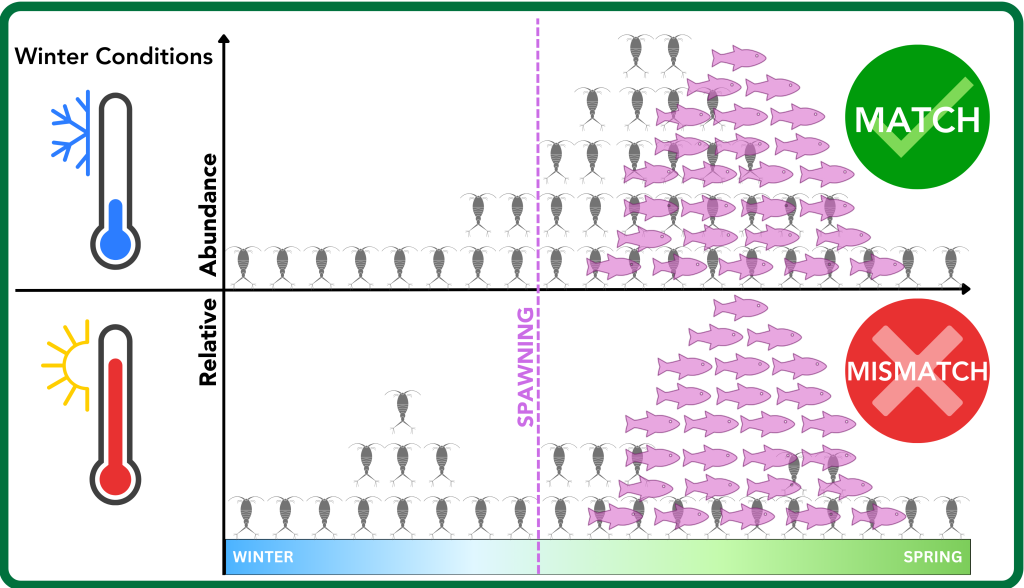

One theory for low spawning success is known as the “mismatch hypothesis.” This suggests that the food source—blooms of cold-water zooplankton—are not matching up with the first time larval striped bass need to eat, as winter temperatures in the Chesapeake increase. If the zooplankton blooms don’t align with the first-feeding larvae, feeding success is too low for good survival.

Warm winters and low flow rates, as well as a shortened spawning window, make things difficult for striped bass, which are sensitive to small changes.

“With temperatures warming up faster, things may not be lining up anymore,” Uphoff said. “That ‘just right’ is a narrow window, and it’s getting narrower.”

According to the mismatch hypothesis, the misalignment of plankton blooms with the first meal of larval striped bass could be causing a decline in juvenile numbers. Graphic by Shannon Moorhead, Maryland DNR.

Recently, Uphoff returned to egg survey data he helped collect for DNR decades ago and published research suggesting that poor larval survival was a driving factor in the 1970s collapse of Chesapeake Bay striped bass.

Conservative management of the fishery aided in the recovery at the time, because a larger stock of adults allows for greater spawning success when conditions are right. But Uphoff said information on what’s affecting the species at the egg and larval stage is critical to understanding the challenges that striped bass face.

Last year, the team found that the larvae did seem to eat well, and that larval mortality was more likely a direct result of temperature changes. But the team is continuing to collect data to determine how much mismatched zooplankton blooms are affecting low larval survival and what other factors are contributing to spawning success. Uphoff said they’re hoping to publish a study on this year and last year’s larval feeding.

“The spawn only happens once a year, so we really need to collect data when we can,” Uphoff said. “If we have two years of data, at least we have something. We haven’t sat on our hands. We’re trying to put some data out there, because if you have some information that could help management and help people understand.”

By Joe Zimmermann, science writer with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.