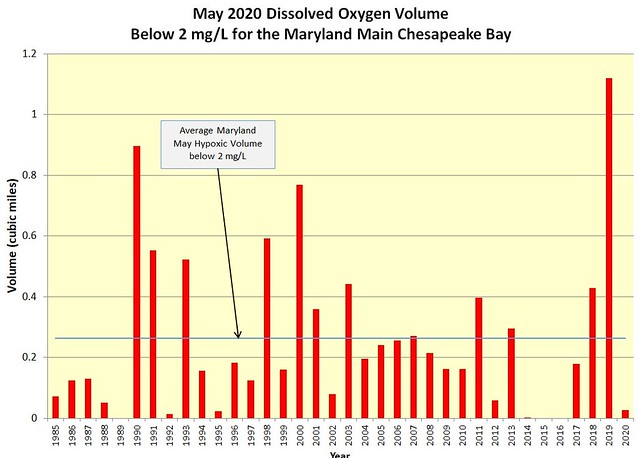

Maryland Department of Natural Resources monitoring data show that dissolved oxygen conditions in the Maryland portion of the Chesapeake Bay mainstem were better than expected in May 2020. The hypoxic water volume — waters with less than 2 mg/l oxygen — was 0.027 cubic miles, which is well below the May 1985-2019 average of 0.25 cubic miles, and an improvement from the 1.12 cubic miles of hypoxia observed in May 2019. No anoxic zones— waters with less than 0.2 mg/l oxygen — were observed.

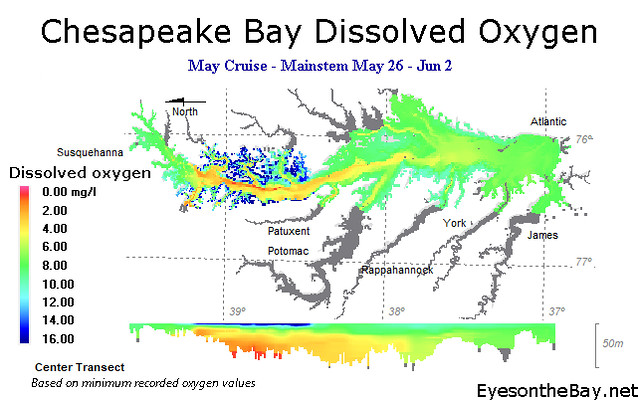

Maryland Department of Natural Resources monitoring data show that dissolved oxygen conditions in the Maryland portion of the Chesapeake Bay mainstem were better than expected in May 2020. The hypoxic water volume — waters with less than 2 mg/l oxygen — was 0.027 cubic miles, which is well below the May 1985-2019 average of 0.25 cubic miles, and an improvement from the 1.12 cubic miles of hypoxia observed in May 2019. No anoxic zones— waters with less than 0.2 mg/l oxygen — were observed.Hypoxic volumes were smaller than expected, likely due to a cooler-than-average spring. Cooler waters are able to hold more oxygen and water column temperatures were also more homogeneous (less stratified) from top to bottom, allowing more oxygen to mix into deeper waters. Water quality data can be explored with a variety of online tools at the department’s Eyes on the Bay website.

These results mark the return of DNR field crews monitoring Maryland waters after a hiatus that started mid-March, following COVID-19 emergency measures. Crews are adhering to social distancing and safety protocols to provide resource managers, scientists, and the public with timely water quality results that drive Chesapeake Bay restoration.

These results mark the return of DNR field crews monitoring Maryland waters after a hiatus that started mid-March, following COVID-19 emergency measures. Crews are adhering to social distancing and safety protocols to provide resource managers, scientists, and the public with timely water quality results that drive Chesapeake Bay restoration.Later in June, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program, U.S. Geological Survey, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, and University of Michigan scientists will release their annual forecast for 2020 hypoxic conditions based on nitrogen loads into the bay from January to May 2020.

Crabs, fish, oysters, and other creatures in the Chesapeake Bay require oxygen to survive. Scientists and natural resource managers study the volume and duration of bay hypoxia to determine possible impacts to bay life. Each year from June through September the Maryland Department of Natural Resources computes these volumes from data collected by Maryland and Virginia monitoring teams during twice-monthly monitoring cruises. Data collection is funded by these states and the Chesapeake Bay Program.