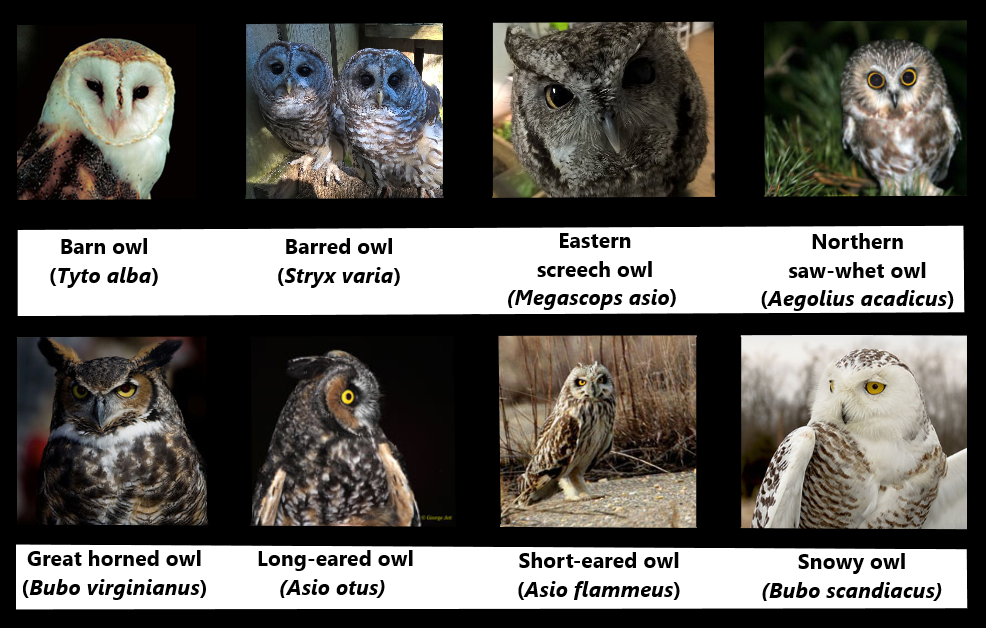

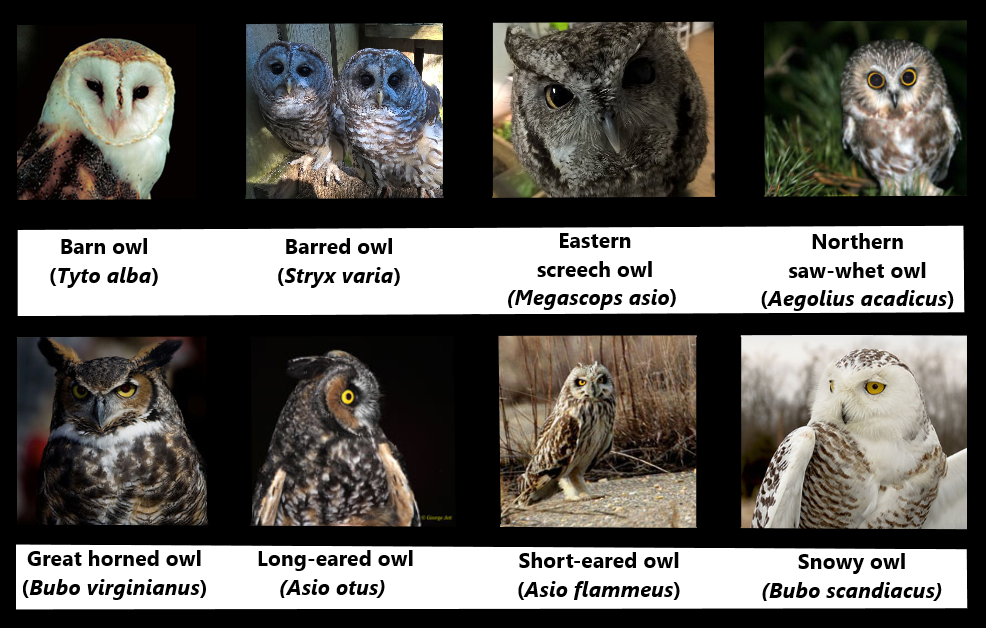

Out of the eighteen species of owls found throughout North America, there are eight species of owls seen in Maryland. Some are very common, such as the eastern screech owl or barred owl, yet some can only be seen occasionally in the winter or during migration, like the majestic snowy owl and the short-eared owl.

While owls like the great horned owl and barred owl spend time in Maryland year-round, it is a bit easier to spot them in the winter when there is less foliage to hide them from sight. Owls are efficient predators and have excellent nocturnal eyesight. Even though they can’t move their eyes like humans, they have flexible necks that allow them to rotate their heads up to 270 degrees.

Owls also have a well-developed sense of hearing. Due to facial feathers arranged as a disk and asymmetric ear openings, they can hear faint sounds like grasses and dry leaves rustling and be able to accurately pinpoint the direction of the incoming sound.

When compared to fast-flying raptors like hawks and falcons, owl feathers are abundantly soft. This quality facilitates their ability to fly quietly and undetected by their prey, which consists of small mammals, snakes, birds, insects, and other animals. Once prey is caught in the owl’s talons, they have little chance of escape, since great horned owls can exert forces of up to 750 psi at the tips of their talons, compared to humans who can exert about 125 psi of pressure.

It is finally January and we are in full winter mode in Maryland. How do owls survive in the winter? They don’t hibernate, but half the species found in Maryland often migrate to or through our state. These are the northern saw-whet owl, snowy owl, long-eared owl, and short-eared owl. That said, most individuals don’t migrate, and even those that do shift their ranges to more southern latitudes remain in places that are fairly cold in the winter. Their bodies are covered with extra layers of fluffy down feathers, and like most birds, they also have feet that adapt to cold weather. Their feet don’t retain a lot of fluid, making them harder to freeze, and they have limited pain receptors in them, which makes it easier for the owls to hunt or carry on with their daily lives comfortably. Some owls like the snowy owl also have feathers on their legs for added insulation. Their feet, like most birds, also have something called a countercurrent heat exchange system that minimizes heat loss. Lastly, because of the way their ear openings are designed, they can hear prey even underneath the snow, which means that these creatures are great at surviving even the harshest winters.

To learn more about Maryland’s owls, please visit our page Owls of Maryland – Maryland’s Wild Acres. You can also discover information on how to make your backyard “owl friendly” with our Habitat Tips: Owl-Friendly Backyards and look at past research into saw-whet owls by checking out: The Secret Saw-Whet: Hiding in plain sight.

Welcome HabiChatters to the 2023 winter issue!

In this issue, Education Ecologist Paula Becker starts us off with a fantastic overview of what is happening in the natural world at this time of year, and then I’ll tell you some of what we’re up to in the Natural Heritage Program. Education Assistant Edwin Guevara writes about some of our favorite winter wildlife, owls and evergreens. And, if our newsletter didn’t fully feed your craving for reading, I’ve included a reading list to inspire and delight. We hope you enjoy and wish you a very Happy New Year from the education team at Wild Acres!

Click here to have HabiChat—the quarterly backyard wildlife habitat newsletter from the Wild Acres program—delivered right to your inbox!

In this Issue

While owls like the great horned owl and barred owl spend time in Maryland year-round, it is a bit easier to spot them in the winter when there is less foliage to hide them from sight. Owls are efficient predators and have excellent nocturnal eyesight. Even though they can’t move their eyes like humans, they have flexible necks that allow them to rotate their heads up to 270 degrees.

Owls also have a well-developed sense of hearing. Due to facial feathers arranged as a disk and asymmetric ear openings, they can hear faint sounds like grasses and dry leaves rustling and be able to accurately pinpoint the direction of the incoming sound.

When compared to fast-flying raptors like hawks and falcons, owl feathers are abundantly soft. This quality facilitates their ability to fly quietly and undetected by their prey, which consists of small mammals, snakes, birds, insects, and other animals. Once prey is caught in the owl’s talons, they have little chance of escape, since great horned owls can exert forces of up to 750 psi at the tips of their talons, compared to humans who can exert about 125 psi of pressure.

It is finally January and we are in full winter mode in Maryland. How do owls survive in the winter? They don’t hibernate, but half the species found in Maryland often migrate to or through our state. These are the northern saw-whet owl, snowy owl, long-eared owl, and short-eared owl. That said, most individuals don’t migrate, and even those that do shift their ranges to more southern latitudes remain in places that are fairly cold in the winter. Their bodies are covered with extra layers of fluffy down feathers, and like most birds, they also have feet that adapt to cold weather. Their feet don’t retain a lot of fluid, making them harder to freeze, and they have limited pain receptors in them, which makes it easier for the owls to hunt or carry on with their daily lives comfortably. Some owls like the snowy owl also have feathers on their legs for added insulation. Their feet, like most birds, also have something called a countercurrent heat exchange system that minimizes heat loss. Lastly, because of the way their ear openings are designed, they can hear prey even underneath the snow, which means that these creatures are great at surviving even the harshest winters.

To learn more about Maryland’s owls, please visit our page Owls of Maryland – Maryland’s Wild Acres. You can also discover information on how to make your backyard “owl friendly” with our Habitat Tips: Owl-Friendly Backyards and look at past research into saw-whet owls by checking out: The Secret Saw-Whet: Hiding in plain sight.

Welcome HabiChatters to the 2023 winter issue!

In this issue, Education Ecologist Paula Becker starts us off with a fantastic overview of what is happening in the natural world at this time of year, and then I’ll tell you some of what we’re up to in the Natural Heritage Program. Education Assistant Edwin Guevara writes about some of our favorite winter wildlife, owls and evergreens. And, if our newsletter didn’t fully feed your craving for reading, I’ve included a reading list to inspire and delight. We hope you enjoy and wish you a very Happy New Year from the education team at Wild Acres!

Click here to have HabiChat—the quarterly backyard wildlife habitat newsletter from the Wild Acres program—delivered right to your inbox!

In this Issue

- In Praise of Dormancy

- Natural Heritage Program’s Winter Work: Revisiting Maryland’s Tiger Salamanders

- Native Plant Profile: Evergreens

- A Cozy Winter Reading List for 2023