Secretary Josh Kurtz assists with a trout survey in the Gunpowder River. Maryland Department of Natural Resources photo.

Science is the foundation of everything we do at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. To emphasize this point, DNR conducted its second annual Science Week from Sept. 23 to 27 to highlight the department’s field experts working to conserve and protect our lands, waters, and wildlife.

During this week I traveled more than 500 miles with department leaders from locations in western Maryland to the southern Eastern Shore to join our department’s field staff and view their work firsthand.

One of our visits was to the Cooperative Oxford Laboratory, a critical center for research on aquatic health run by scientists from DNR and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Working in an unassuming building nestled in the charming waterfront town of Oxford, scientists focus on marine animal disease and environmental threats to Maryland waters.

The center was created in the 1960s to study oyster diseases like MSX and Dermo, which remains one of the facility’s primary operations. Biologists carefully monitor Chesapeake Bay populations of oysters for prevalence of these diseases by analyzing tissue samples.

Other biologists are studying the spread of mycobacteriosis among striped bass to help protect and manage Maryland’s state fish. The lab is also home to the Maryland Marine Mammal and Sea Turtle Stranding Response Program, who work as part of a national network to investigate strandings of rare and endangered sea turtles, whales, dolphins, and other animals in Maryland waters.

Elsewhere during Science Week, we explored the hard work that goes into monitoring the Chesapeake Bay.

Staff from DNR’s Resource Assessment Service demonstrated several techniques they use for monitoring the waters of the Chesapeake and the Bay bottom. DNR staff deploy a research vessel to sites across the Bay throughout the year in order to take readings on water quality including dissolved oxygen levels, pH, and water temperature, as well as measure the amount of nutrients and sediment in the water. This data helps to inform Maryland’s Eyes on the Bay online reports and the department’s regular reports on hypoxia.

DNR staff also conduct mapping of Bay bottom habitats. They cross areas of the Bay back and forth–similar to “mowing the lawn”–on a research vessel that pulls several pieces of sensing equipment: a side-scan sonar, a seismic sub-bottom profiler, and a marine magnetometer. Together, these give the team a comprehensive map that reveals the structure and material of the Bay bottom. This gives us information on potential locations for oyster restoration, and it can even reveal shipwrecks or interesting areas for archeological excavation.

Science Week 2024 is documented as a story in DNR’s Instagram account.

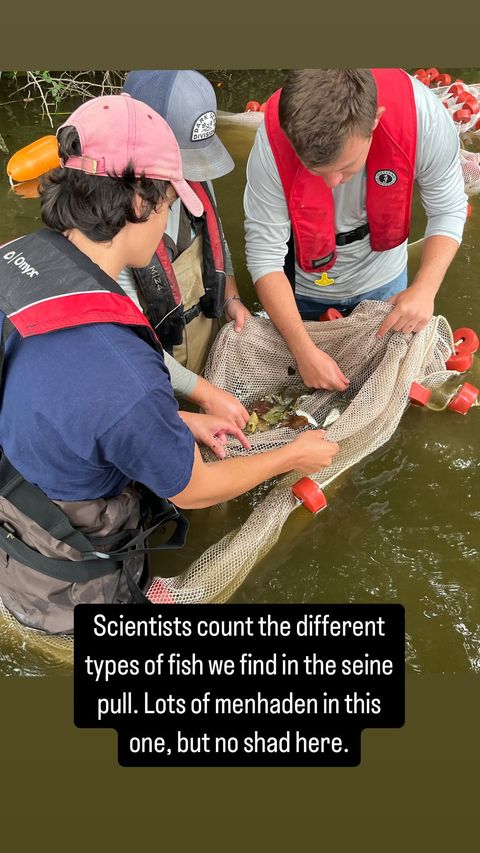

Keeping an eye on the Bay also requires monitoring its tributary system, in particular the species that live in Maryland’s rivers and streams. During Science Week, we joined fisheries biologists on the Choptank River for the final day of this year’s shad survey. The survey looks for juvenile American and hickory shad to assess the survival of hatchery-raised shad larvae and fingerlings as well as wild reproduction.

In this survey, biologists collect samples at ten sites on tributaries the restoration project is targeting. They deploy a 200-foot seine net at each site. Team members pull in the net by hand, count the number of fish of each species, and collect a subsample of shad to determine if they were stocked by the department or a result of wild reproduction. Through this process scientists hope to see the proportion of wild shad grow, indicating that wild reproduction is occurring and allowing natural population growth.

Another survey by fisheries biologists covered the Upper Gunpowder Falls trout population between Prettyboy Reservoir and Loch Raven Reservoir. Electrofishing crews analyzed and released more than 200 wild brown trout, northern hognose suckers, white suckers, blue ridge sculpin, pumpkinseed sunfish, and American eel in a quarter-mile stretch of the stream.

The population is measured annually and assesses the overall health of Central Maryland’s most popular self-sustaining brown trout fishery. Early assessment of the 2024 population reveals above-average young of year, indicating a successful spawning period, and a healthy overall population.

Ultimately, all this work informs our plans for policy and managing the resources in our care. Water doesn’t stop flowing at state boundaries, so our work to improve the health of the Chesapeake Bay must be done through a strong partnership with other states in the region.

Also in September, I joined Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) Secretary Cindy Adams Dunn to tour water quality projects and explore opportunities for new and improved trail connections on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. I was proud to stand with Secretary Dunn to strengthen our plans to work together, share information, and speed up progress toward restoring the Chesapeake Bay.

Through it all, Maryland DNR scientists will be monitoring that progress.

Josh Kurtz is Secretary of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.