Photo by

On a drizzly day in late September, a crew of Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) biologists cast off from a dock in Denton to survey the Choptank River for juvenile American shad (Alosa sapidissima).

The native fish was once a staple of commercial and recreational fishing in the Chesapeake Bay. Their population plummeted in the first half of the 20th century due to overfishing, habitat degradation, and dam construction. Today, DNR stocks and monitors American and hickory shad as part of a decades-long effort to revive self-sustaining populations of these two species.

“The commercial and recreational fisheries for shad have been closed in Maryland since 1980, but anglers we meet in the course of our work remember when shad were plentiful,” said Anadromous Restoration Project Leader Ashlee Horne. “They share stories of eating shad roe in the style of scrambled eggs and fishing for shad with loved ones. These encounters reflect the cultural relevance of this fishery beyond its ecological importance.”

A few hundred yards downriver is one of 10 survey locations on the Choptank that the crew monitors annually. They assess the survival of the millions of hatchery-raised American shad larvae and fingerlings stocked by the department, and study instances of wild reproduction.

The survey boat navigates right up to the shore and most of the crew hops off into the waist-high water. They use a 200-foot seine net to collect fish from the river by anchoring the net on shore and then deploying it around in an arch by boat.

Team members pull in the net by hand, count the fish of each species, and collect a subsample of shad caught. They recorded 16 American shad on this day of surveying and encountered 290 American shad throughout the 2024 survey season.

Shad are anadromous fish that hatch and spawn in freshwater, but spend most of their lives in the ocean. Scientists believe adult shad spend three to seven years at sea before they return to their natal waterway for spawning, but little is known about their lives there.

The lack of spawning adults has been the biggest underlying challenge to growing the shad population in Maryland despite 30 years of restoration. Scientists believe shad are density-dependent spawners, meaning they need to be in a large group to spawn. Stocking efforts conducted by the state attempt to bring the mass of adults up high enough that natural breeding occurs.

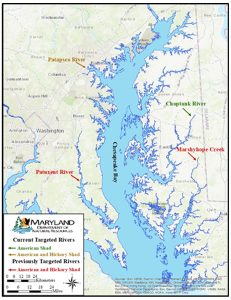

DNR’s stocking efforts have led to the restoration of hickory shad in both the Patuxent and Choptank rivers.

To gauge how stocked and wild fish are faring in the Chesapeake Bay, DNR staff conducting this survey need to know if the shad they catch originated at the state hatchery or if they are a result of wild reproduction. This is where things get technical.

As shad larvae grow at the state’s Joseph Manning hatchery, they are placed in a bath of the chemical oxytetracycline (OTC). Larvae grow rapidly and uptake the chemical into their bodies, including the only bone that has formed at this developmental stage – their ear bones, called otoliths. The chemical leaves a mark on the bone, but when administered properly it is not harmful to fish. Like growth rings on a tree, each bath in the OTC leaves one ring in the bone, and the scientists use multiple baths at specific intervals to create a series of rings that they can read later.

In the winter after the survey season, biologists remove the otoliths, sand them with fine 400-grit sandpaper to expose the marked area, and examine them under an ultraviolet microscope. Based on the presence or absence of markings, the scientists determine if the fish originated at the hatchery and survived in the water post-release or hatched in the wild. Unique marking patterns also reveal at what life stage the fish was stocked.

In the Choptank River, the survey team found in 2023 that 26% of juvenile American shad were naturally occurring and 74% were from the stocked population.

In the Choptank River, the survey team found in 2023 that 26% of juvenile American shad were naturally occurring and 74% were from the stocked population. Electrofishing and gillnetting surveys in the spring examine the origins of adult shad. Over time program managers hope to see the proportion of wild adults grow, indicating that shad are returning to Maryland rivers to spawn and wild reproduction is allowing the population to grow naturally. The goal is to achieve 25% to 75% stocked vs. wild hatched. These proportions are considered healthy enough to result in a sustained population.

Most recently, the department has turned its restoration efforts to the Patapsco River, where it began stocking in 2012. Researchers have seen promising results; 2023 was the seventh year that hatchery-stocked American shad were observed returning to the Patapsco River as adults.

Some of the same threats that led to the decline and suppression of American and hickory shad populations through the 20th and into the 21st century still exist. Habitat challenges and commercial bycatch plague the species. There are also new hazards in the water. Invasive blue catfish are flourishing in the Chesapeake Bay and all of its tributaries and scientists have observed whole hickory shad in the stomachs of these voracious predators.

Only catch-and-release shad fishing is currently legal in Maryland and is popular in the Susquehanna River. Creating a sustainable recreational fishery for the two native shad species is the intent of Maryalnd’s shad stocking program, which is supported by federal Sport Fish Restoration funds.

The service that shad provide in the ecosystem, as a prey species that feeds economically and ecologically important species such as striped bass, is an added benefit to the work.

As the juvenile shad survey season wraps for these biologists, there is still plenty of shad restoration work to be done. The remainder of the year’s work includes collecting, spawning, stocking, and studying shad in an effort to resurrect this historically significant Maryland fishery.

By Sinclair Boggs, Marketing Strategist with Maryland Department of Natural Resources Fishing and Boating Services