Climate change makes region more hospitable to some newcomers—and more difficult for native species

White ibises have started to nest at Martin National Wildlife Refuge.

A Salisbury man fishing for spotted sea trout Sept. 17 in the Chesapeake Bay pulled in a tall, silvery fish with a striking yellow underside.

It turned out to be the largest Florida pompano recorded in the state. It was also a living indication of a warming climate.

The Florida pompano is just one of multiple species of animals, largely fish and birds, that are appearing in the state more frequently at least partially as a result of climate change. Though these newcomers can increase biodiversity and generate excitement among residents and fishermen, scientists caution that they are also warning signs of a changing ecosystem.

“It’s a sign that things are changing enough to cause shifts in distribution,” said Gwen Brewer, a science program manager with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources’ Wildlife and Heritage Service. “We know not everything is going to adjust to those shifts in a positive way. Some species are going to be threatened by those changes.”

Some notable animal sightings, like the manatee that wandered through the Bay in August, represent one individual rather than a trend. But the sheer numbers of others are hard to ignore.

Maryland waters have seen a marked increase of fish associated with warm water such as the pompano, Atlantic cutlassfish, cobia, red drum, sheepshead, spotted sea trout and pompano dolphinfish (a relative of the mahi-mahi), said Erik Zlokovitz, DNR’s recreational fisheries coordinator. Common species like the black sea bass and summer flounder are shifting northward, and a DNR pilot program is allowing watermen to trawl the waters off Ocean City for shrimp for the first time this fall.

Bobby Graves poses with the state record Florida pompano. Photo courtesy Bobby Graves, used with permission.

Lenny Rudow, of FishTalk Magazine, said there’s “absolutely no question” that “things are changing” for fish in Maryland waters. Many fishermen are catching species they’re not used to, and this August he was on a boat that caught 59 cutlassfish in three hours. Cutlassfish only began to show up in higher numbers here in 2019.

“It’s almost like the Bay is shifting into something more like the Pamlico Sound,” Rudow said, referring to the estuarine lagoon in North Carolina.

Jim Uphoff, a DNR fisheries biologist, said other weather patterns could be contributing to the shifting fish populations through decreased freshwater flow and higher salinity, but that these changes are “fairly consistent with what you would expect from warming.”

And data shows warming is taking place. Air temperatures in the state have risen by 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit since the start of the 20th century. DNR researchers collect data at dozens of monitoring stations across the Chesapeake Bay, and most stations record an increase of between 1 and 2 degrees Fahrenheit since the mid-1980s.

“What we’re seeing is these periods are warmer than normal temperatures, longer than normal, and recurring more frequently,” said Tom Parham, director of DNR’s Tidewater Ecosystem Assessment.

While the larger numbers of warm-water fish do not typically disrupt the local food chain, the warming temperatures that attract them could present difficulties for native fish, Zlokovitz said. He’s concerned that other conditions associated with warming, such as dry and hot winters, could have negative impacts on the spawning success of anadromous fish such as striped bass, white perch, shad and herring.

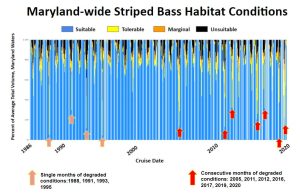

Long-term Chesapeake Bay water monitoring results indicate an increased frequency and severity of degraded resident striped bass habitat.

Striped bass, also known as rockfish, have faced a decline in the Bay since 2019. Though many factors contribute to the reduction, hotter waters limit the area of the Bay that is viable for rockfish.

Warmer water holds less oxygen, and the rising temperatures have created larger pockets of the Bay where striped bass are not able to survive, Parham said.

Maryland’s streams and rivers have seen rises in temperature that exceeded those observed in air and tidal waters, said John Mullican, a program manager with DNR’s freshwater fisheries program. While climate change contributes to the heated waters, so do other factors such as loss of tree canopy and larger areas of impervious surfaces that increase and warm stormwater runoff.

Dan Goetz, manager of statewide operations for DNR’s freshwater fisheries, said the increased temperatures haven’t brought new fish into the freshwater system but have constrained the habitable zones for native fish, like brook trout.

“Brook trout are already restricted to the coldest parts of the stream, so if temperatures exceed their thermal limit, they eventually die out in that area,” Goetz said. “There is nowhere for them to go.”

On the terrestrial side, animals tend to be slow in moving to different locations, Brewer with Wildlife and Heritage Service said. But warming climates have brought changes.

Some birds have started breeding in the state in the past few years, due to developments that are likely linked to climate change, said Gabriel Foley, coordinator of the Maryland & DC Breeding Bird Atlas that tracks birds breeding in the state. White ibises have been seen nesting in Martin National Wildlife Refuge, and breeding anhingas have started to show up in the Patapsco Valley. Mississippi kites, a small insect-eating hawk, have nested in three Maryland counties.

Other typically southern birds, like the painted buntings that caused a stir in 2021 or a wayward wood stork in the C&O Canal, have passed through the state, but don’t have a breeding presence here.

More noticeable than the new birds, however, is the effect that climate change is having on extant species in the state, Brewer said. Sea-level rise has contributed to habitat loss, especially for breeding birds. For example, there were no black skimmers recorded breeding in the state last year because of lost nesting ground.

A painted bunting eats a pokeberry in Maryland. Photo by Sherri Powers.

Then, there are the pathogens that come hand-in-hand with global warming. Mosquitoes thrive in hotter temperatures and bring with them diseases like West Nile virus, contributing to the decline of the ruffed grouse. Climate change may also exacerbate the spread of avian flu, which continues to be a scourge for birds globally.

While it can be difficult at the state level to tackle global temperature increases, scientists say that mitigation and adaptation efforts can create better conditions for native species as the ecosystem changes.

The state is planting more than five million trees, which help provide cooling canopy for habitats and streams and also set up long-term carbon sequestration, said Anne Hairston-Strang, the acting state forester for the Maryland Forest Service.

DNR’s Environmental Review Program assesses land use and development projects to avoid or mitigate impacts to the environment and wildlife, and DNR’s Chesapeake & Coastal Service works to build back healthier habitats through restoration projects such as living shorelines.

Brewer pointed to projects like the artificial tern island built to replace lost habitat in Chincoteague Bay in 2021 as a short-term solution to keep populations going until habitat can be restored, while further efforts can aim at reducing other stressors for animals and plants.

“We can usually do something about the other threats that are facing those species,” Brewer said. “That’s something we can focus on rather than throwing up our hands and saying, ‘Well we can’t do anything because it’s climate change.’ We try to make the situation as good as it can be for the species that are there while they are trying to persist in the face of changing conditions.”