Here’s what we do know. Iron-oxidizing bacteria gain energy to live and grow by transforming dissolved iron into an insoluble form of iron oxide — better known as plain old rust. (It’s actually an incredibly difficult thing to accomplish, because iron has so little energy to offer in the first place.) Scientists find these microorganisms in a bunch of different environments: freshwater, saltwater, even in streams and ditches along the side of the road.

But in a deep-sea environment they prefer to nestle in the iron-rich sediments on the ocean’s floor, says Field, who works to identify the microbial communities associated with steel-hulled shipwrecks along the Pamlico Sound and Neuse River systems in North Carolina. “When a wreck occurs and reaches the bottom of the ocean, you get mixing of the water and sediment from that disturbance. That allows the microbes in the sediment to get into the water column and potentially attach onto the new habitat that has arrived,” she says.

The Titanic, which contained tens of thousands of tons of steel, was a downright feast for these bacteria.

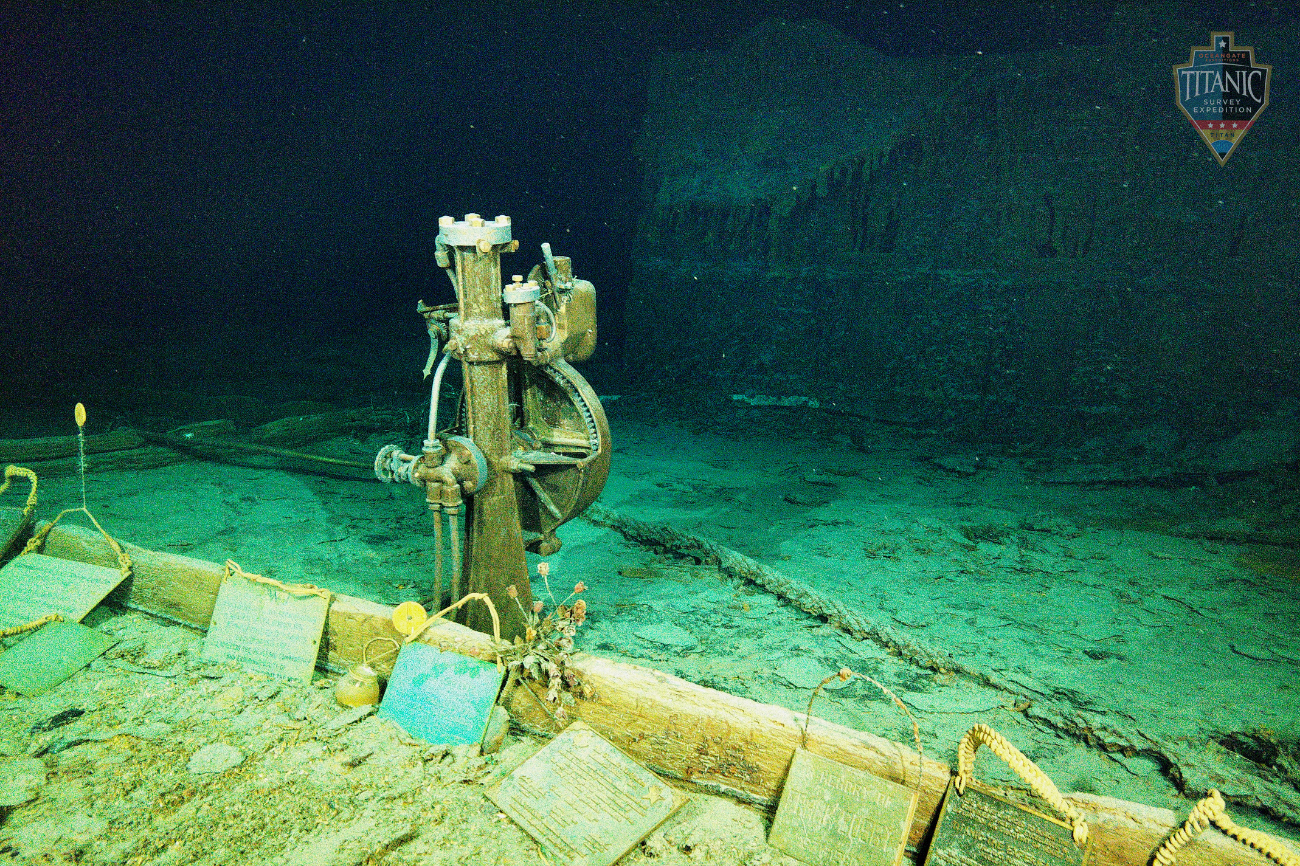

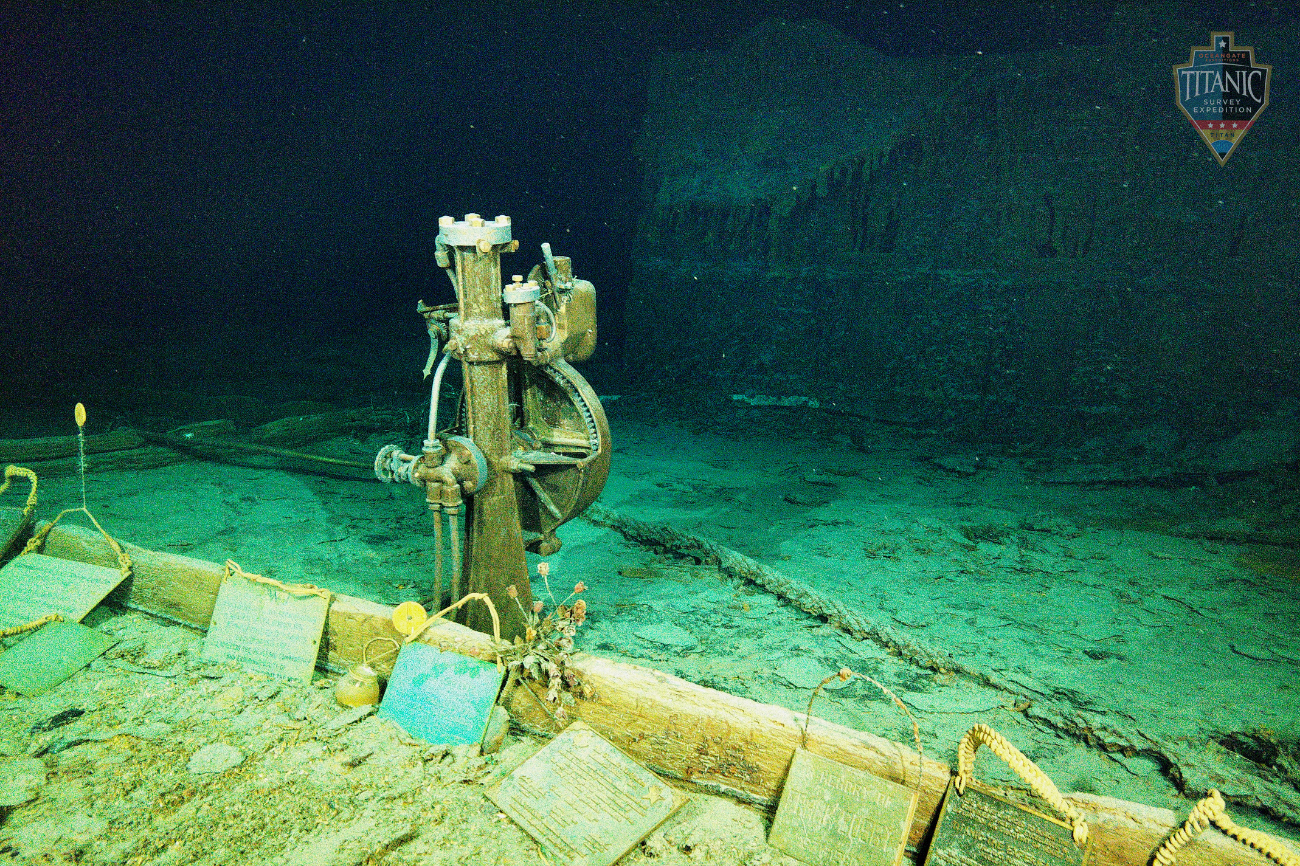

We can see evidence of this feasting from the rusticles, so dubbed because they resemble icicles made of rust, that now litter its surfaces. Some of the iron-rich formations have grown as tall as a person. “The colors are just incredible with the rusticles — the reds and oranges and blues and greens. You don't see that, typically, on other wrecks that I've been on that are shallow,” says Stockton Rush, CEO and founder of OceanGate. “The wrecks don't tend to have quite the color palette that the Titanic does.”

www.discovermagazine.com

www.discovermagazine.com

But in a deep-sea environment they prefer to nestle in the iron-rich sediments on the ocean’s floor, says Field, who works to identify the microbial communities associated with steel-hulled shipwrecks along the Pamlico Sound and Neuse River systems in North Carolina. “When a wreck occurs and reaches the bottom of the ocean, you get mixing of the water and sediment from that disturbance. That allows the microbes in the sediment to get into the water column and potentially attach onto the new habitat that has arrived,” she says.

The Titanic, which contained tens of thousands of tons of steel, was a downright feast for these bacteria.

We can see evidence of this feasting from the rusticles, so dubbed because they resemble icicles made of rust, that now litter its surfaces. Some of the iron-rich formations have grown as tall as a person. “The colors are just incredible with the rusticles — the reds and oranges and blues and greens. You don't see that, typically, on other wrecks that I've been on that are shallow,” says Stockton Rush, CEO and founder of OceanGate. “The wrecks don't tend to have quite the color palette that the Titanic does.”

Bacteria Are Eating the Titanic

Batten down the hatches! Will a rusticle forming bacteria called Halomonas titanicae completely disintegrate the Titanic shipwreck within our lifetime?