A new study looks at the age at which female striped bass mature and how many eggs they produce as they age

Department of Natural Resources fisheries biologists survey for striped bass in 2018. Photo by Stephen Badger, Maryland DNR.

Two of the most important traits to understand fish population growth are the age at which females mature and their fecundity, or how many eggs they can produce at each age on average.

A new study from biologists in the Maryland Department of Natural Resources has helped to update information on those factors in striped bass, making available current biological information about the population for use in the stock assessment model, which estimates the numbers and biomass of mature females in the Atlantic coast striped bass stock.

The study, published in Marine and Coastal Fisheries: Dynamics, Management, and Ecosystem Science in February, determined that half of females reach sexual maturity between ages 5 and 6, and larger, older females produce more eggs per kilogram body mass than smaller, younger females.

“This research demonstrates the importance of protecting the female breeding stock of striped bass, both throughout their life cycle and particularly when they are at large, productive sizes,” said Lynn Fegley, director of the department’s Fishing and Boating Services. “By protecting large female striped bass, we can help make sure they produce a lot of eggs that will survive better when the environmental conditions are right for successful spawning.”

This study sought to use updated methods to define maturity and explore whether weight and fecundity were proportional when estimating the size of the striped bass spawning stock.

Three Maryland Department of Natural Resources biologists—Simon Brown, Angela Giuliano, and Beth Versak—examined the microscopic anatomy of striped bass ovaries to better understand specific aspects of the reproductive biology of female Atlantic striped bass.

The biologists used the latest standards in applying histology—the microscopic study of tissues—to identify maturity in fish, standards which have progressed since the last time the female age-at-maturity schedule used previously in the assessment was calculated. They then analyzed striped bass ovaries to distinguish between immature, maturing and functionally mature developmental stages.

Through collaboration with multiple state and federal agencies, surveyors collected a wide range of samples throughout the fall and the entire spring spawning season in the Chesapeake Bay and Atlantic Coast, accounting for all developmental stages.

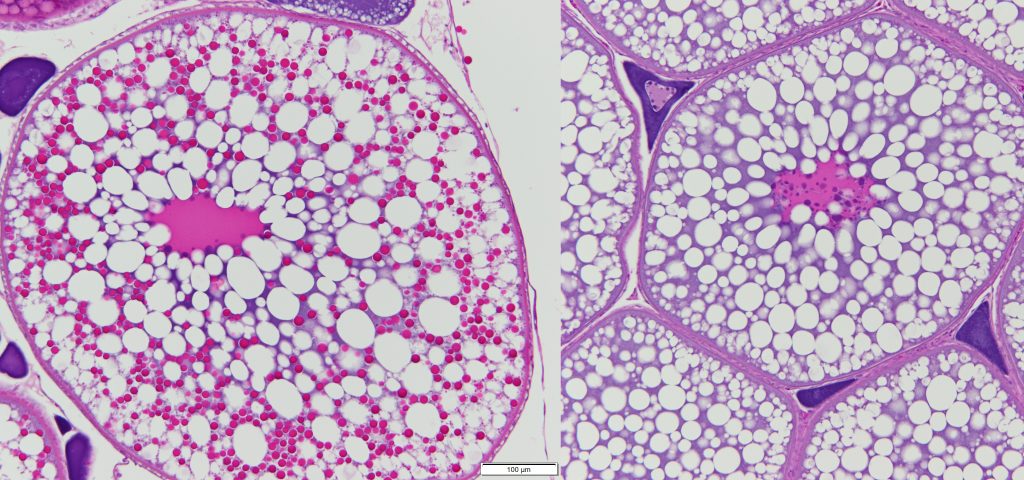

Scientists at the Oxford Cooperative Laboratory then stained cross sections of striped bass ovaries with special dyes, encased them in paraffin wax, and mounted thin slices on a glass slide. The dye highlights different components of the developing eggs, allowing biologists to determine if a striped bass could produce fully developed eggs by the spawning season, or had just recently spawned.

Close-up images of striped bass oocytes (developing egg) from histologically prepared ovarian tissue samples collected during the spawning season. From left to right: an oocyte from a functionally mature individual containing numerous vitellogenin-derived yolk protein granules (red dots) and an oocyte from a maturing individual that will not spawn this season. The transparent sponge-like areas of the oocyte are the neutral lipids that aid in egg buoyancy as striped bass eggs float in the water column until hatching.

The authors found that some younger females produced enlarged oocytes (developing eggs) that appeared developed but lacked the critical yolk material. These were determined to be fish that had begun maturing, and go through a “practice” reproductive cycle, but hadn’t yet become fully mature adults capable of reproducing. As water temperatures rise in June, the unspawned, unreleased eggs are reabsorbed in a process called atresia. The resulting analysis showed that just a small percentage of females reach maturity by age 4, but about 90% do by age 7.

The female age-at-maturity schedule is used in the stock assessment to calculate spawning stock biomass but was previously estimated during the 1980s when the stock was considered collapsed. This study determined the female age and length at 50% maturity in Atlantic striped bass based on spring samples were around ages 5 and 6 and 24 inches long. The updated maturity schedule was used in the last benchmark stock assessment for striped bass.

The researchers determined fecundity by taking a photo of small samples of mature striped bass eggs, using a computer algorithm to count the eggs in the photos, and conducting further calculations to come up with an estimate of the total numbers of eggs found in a ripe striped bass ovary.

The number of eggs produced by a female striped bass ranged up to 4 million in a 13-year-old fish, but eggs also increased disproportionately with body weight. This means, for example, that in one spawning season, a 30-pound striped bass will produce more eggs than two 15-pound striped bass combined.

“Detailed information on the reproductive life history traits that translate female striped bass biomass into reproductive capacity is crucial for informing future management of the stock,” Brown, fisheries biologist and study co-author, said.

While the authors noted methodological and interpretive differences between this study and others ranging over the past decades, the resulting calculations of age at 50% maturity and fecundity were consistent with previous findings. Given that environmental and fishing pressure on spawning striped bass has been variable over the last four decades, this study concludes that reproductive-related life history traits of female Atlantic striped bass are robust to long-term changes.

This research contributes to the department’s effort to understand the spawning challenges striped bass face in the Chesapeake Bay and use the latest science to inform management.

Fisheries managers monitor a variety of factors that influence striped bass recruitment. Environmental conditions, including warm winters and low water flows, have been unfavorable for striped bass recruitment and are considered to be factors behind recent decreased reproductive success. After five consecutive years of below-average spawning success in Maryland’s four major spawning rivers, as well as the stock assessment indicating an overfished status of the Atlantic striped bass stock, Maryland and the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission have approved management actions aimed at protecting the spawning stock and reducing fishing mortality in 2024.

By Sinclair Boggs, Marketing Strategist with Maryland Department of Natural Resources Fishing and Boating Services